New paper on attention during aversive learning

I recently had a new paper published , which is the first project I’ve completed as part of my current fellowship. In this blog post I mainly want to talk about how the whole thing came to exist, along with the challenges I faced along the way. I always find “behind the paper stories interesting, and it’s always reassuring to hear about difficulties others have faces and how they’ve overcome them, rather than simply seeing the final, polished project.

The study

First I’ll summarise the paper. I don’t want to go into too much detail here – you can read the actual manuscript if you’re desperate for details!

Rationale

I’m primarily interested in how dysfunction in aversive learning processes might be involved in anxiety disorders. One repeated finding in anxiety research is that anxious individuals tend to pay more attention to potential threats (e.g. negative facial expressions), but we don’t really know why. My hypothesis was that this could be due to the way people learn about the aversive value of these stimuli (i.e. how unpleasant they are).

What we did

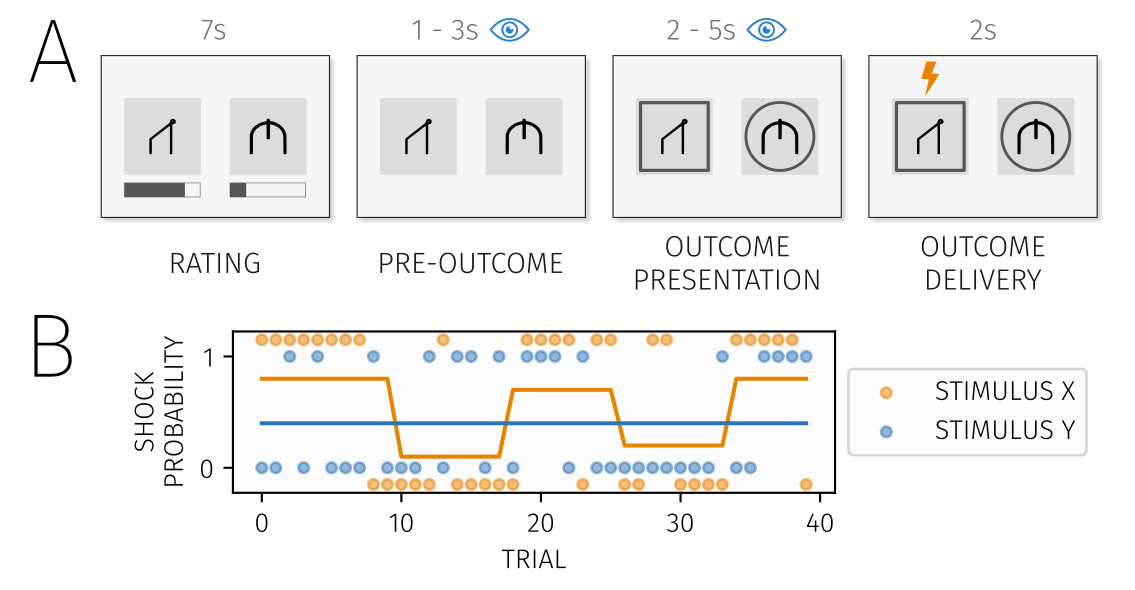

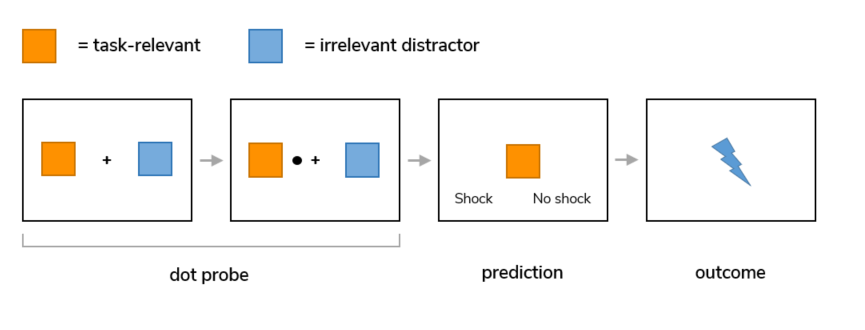

To answer this question we used a relatively simple aversive learning task. Subjects had to estimate the probability of receiving a shock from each of two shape stimuli shown on screen concurrently, and we used computational models to look at how people learned these probabilities, and how they estimated uncertainty around their predictions. We used eye tracking as an index of visual attention while subjects completed this task.

The task

What we found

Subjects paid most attention to stimuli with high aversive value (i.e. those most likely to lead to a shock), but attention was not influenced by how uncertain they were about the shock probability. We also found that attention influenced learning – subjects learned faster about stimuli they paid more attention to. We also found a rather confusing result when looking at relationships with trait/state anxiety – more anxious people tended to learn faster about safety!

Amazingly exciting results

The story

Conception & design

I’ve been interested in attentional bias towards threat for years, so I’m glad to have had an opportunity to try to understand it a little more. I now mostly work on learning in anxiety, and to me it made sense to try to link aversive learning processes to one of the most studied features of pathological anxiety. This project was something I naïvely thought would be a fairly simple – just take an aversive learning task and add on some measure of visual attention, couldn’t be too difficult right?

My very first design idea, which was kind of terrible and would have likely ended in complete failure

My very first design idea, which was kind of terrible and would have likely ended in complete failure

My initial plan was to use a task where subjects learned about two stimuli simultaneously and add in a few dot probe trials to get a reaction time based measure of attentional bias (subjects should react faster to dots shown in the position of the most valuable stimulus). However after a bit of reading I came to realise that the dot probe has a few issues, particularly regarding reliability, and eye tracking seemed like a better idea.

Next came the piloting, which revealed a number of problems that required dealing with:

- Binary choices vs. continuous probability estimates? I’d originally planned to go with binary choices but discovered that modelling worked a lot better with continuous shock probability estimates.

- Timings – how long to show each phase of the trial for? How long to give subjects to make a response? Should timings be jittered to make them less predictable?

- Positions of stimuli – did I want stimulus positions to be random or fixed?

- Task duration – we obviously need as much data as possible but attention tends to lapse pretty quickly, and we can’t shock people forever!

- Instructions – how much can we tell people about what they are supposed to do? A particular problem I encountered (and which I couldn’t really solve without giving people explicit instructions about how to work out the shock probability) was that a number of people used a gambler’s fallacy-like strategy – i.e. if I got shocked last time I’m unlikely to get shocked this time.

Behaviour proved the most difficult to optimise. I wanted to look at how value and uncertainty influenced attention, so I needed a task that required subjects to estimate uncertainty and behave in accordance with this. I also needed models that incorporated estimations of uncertainty (while not being too complex and having recoverable parameters). This required a lengthy iterative process of adjusting the task design and modelling approaches, which was hindered slightly by the fact that I had no idea what I was doing when it came to computational modelling (thankfully my co-authors are far more experienced than I am).

I’m a fan of open science, and I wanted to preregister this study. This didn’t go quite as I’d planned, it ended up being a pretty rushed and vague preregistration and I didn’t write down hypotheses that I felt I hadn’t really thought about in enough detail (one of the main findings in the paper regards attention influencing learning, which I’d planned to look at but when I wrote the preregistration I hadn’t get thought through exactly how I’d do this and so left it out - in future I’ll be more organised). The main reason for doing this however was exclusions – I knew from piloting that I’d have to exclude a few participants and wanted to have these criteria set in stone before beginning. Overall I am incredibly happy I preregistered the study. I can’t count the number of times I went back to the preregistration to remind myself of exactly what I was supposed to be doing!

Analysis

Analysis also presented significant challenges - I ended up using a number of methods I had little prior experience with. Most of the analysis relies on hierarchical Bayesian models, which I felt provided the best way of dealing with the data but which I didn’t know much about at all. Thankfully tools like PyMC3 made this easier than it could have been, but it was still a challenge.

However, as this was a learning experience I inevitably ended up making mistakes along the way which made it a slightly more traumatic experience than it might otherwise have been – and really emphasised to me how easy it can be to innocently generate false positives. My first analysis run produced some quite nice results – in particular, it seemed like more anxious people overestimated uncertainty, which wasn’t too surprising a finding. However, when I came to check over my model fitting I realised that something had gone wrong (which was not obvious to me at all at first) and the model fits were all a little off. Rather sadly, fixing this made my exciting result disappear and it was instead replaced with one that made little sense to me!

At this point, I was quite happy with everything and wrote up a draft manuscript. I’d found that both aversive value and uncertainty influenced attention, which was quite exciting. As I wanted to embrace open science in this project I had decided I wanted to make all my code and outputs available online, and this obviously creates additional pressure to make sure all the code works properly and is (relatively) readable, so I looked over my code thoroughly to check everything in detail. This is a rather code-heavy project, and it’s almost inevitable in this kind of work that bugs will creep in.

This is where I identified a bizarre bug in one of my eye tracking functions that I hadn’t noticed previously. Again, fixing this led to more disappointment – attention was no longer influenced by uncertainty. This is another point at which my decision to follow open science practices has clearly benefited my work – if I’d not planned to make my code openly available I almost certainly would not have checked it in so much detail and probably would never have identified this bug, and as a result the conclusions of the study would be quite different (and wrong!).

What next?

This was a big challenge, but I think resulted in a nice paper with some really interesting results. I learned a lot along the way, including skills that I’ve made good use of in subsequent projects.

One of my main aims is to tie dyfunction in aversive learning processes to symptoms of anxiety disorders. One of the most surprising results from this study is that more anxious people seemed to think that they were generally safer than less anxious people (this ended up tucked away in supplementary material in the paper but I think it’s still really interesting). This is something I’m currently following up on, but my initial work so far seems to suggest that this might not be a spurious result.

Paper: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007341

Preregistration: https://osf.io/8rwcu/

Data: https://osf.io/b4e72/